Strange Truths - Notes and highlights

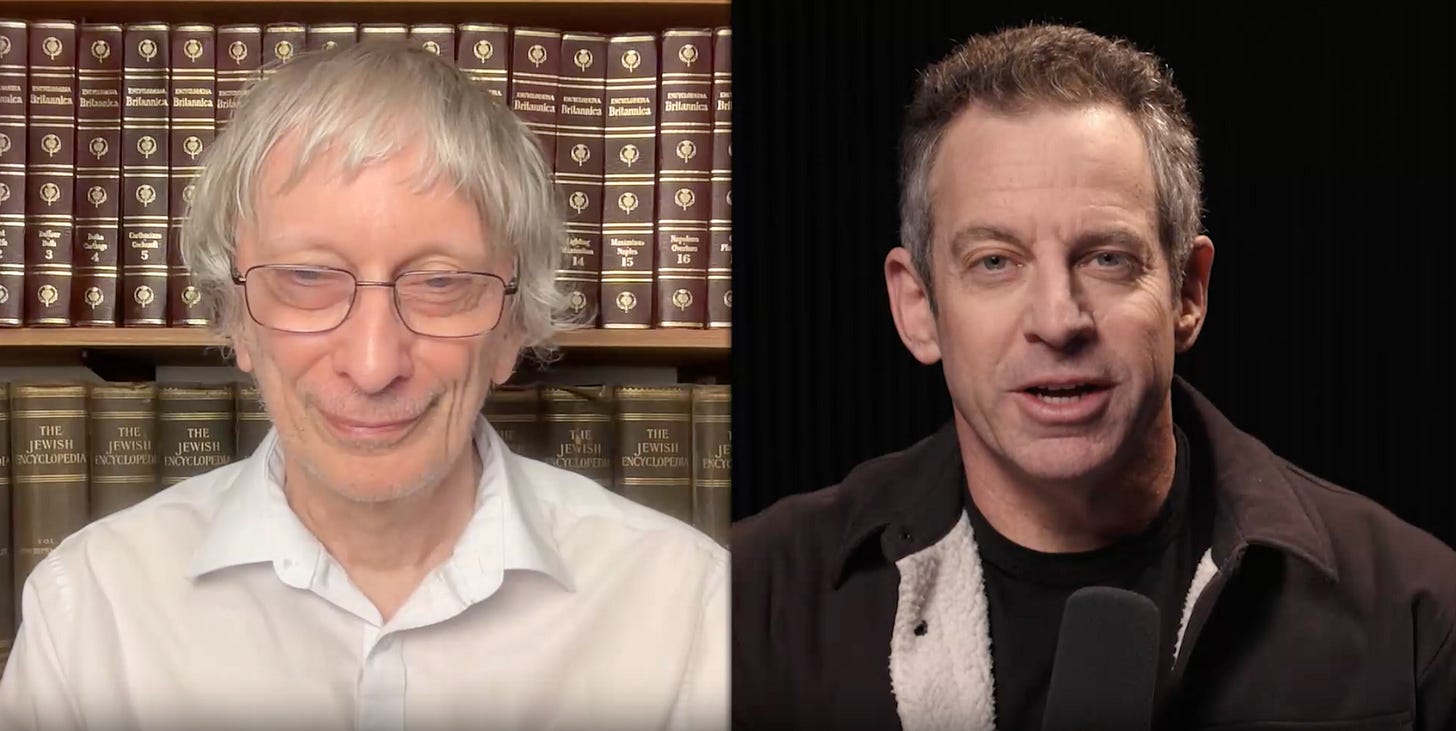

Sam Harris and David Deutsch discuss quantum mechanics, AGI, and the state of the West.

David Deutsch was on Sam Harris’s Making Sense podcast a few weeks ago. The episode title is Strange Truths and Sam and David discussed a number of surprising things that are indeed true, from quantum physics to antisemitism.

Here are some notes and highlights. I’m afraid you won’t find this post particularly useful, it’s mainly a way for me to reflect on the conversation and try to learn something from it. As always, any mistake or misinterpretation is mine.

Thou shalt not prophesy

At the core of David’s 1997 book The Fabric of Reality was the question: what happens if we take our best explanations seriously? Something else David takes seriously is intellectual integrity and the difference between “predictions” and “prophecies”.

Here are just a few quotes in which David declines to comment in depth on a question or topic because he is not an expert on it:

I’m not an expert on human irrationality and fads

I’m not an expert on cryptography

I don’t know how long [we’ll have to wait for AGI]. Let me not prophesy.

These might come across as deflections, but to those who have read his work, they are clear examples of someone who understands that explanations need to come from a place of practiced expertise.

If you don’t have the raw intellectual material to construct an explanation, just admit it and move on—do not prophesy. (Related: Don’t throw the expert out with the bath water)

How bad philosophy derailed progress in quantum physics

David points to positivism as the philosophical roots for the enduring confusion in quantum theory.

The view that took hold was that the only ideas which can be confirmed by experiments are worth preserving. But if one takes that seriously, then dinosaurs never existed because there is no experiment we can make that can confirm them. “God might have put the bone-looking rocks into the ground” is as valid a theory under the positivist framework.

From The Beginning of Infinity:

Although there have been signs of improvement since the late twentieth century, one legacy of empiricism that continues to cause confusion, and has opened the door to a great deal of bad philosophy, is the idea that it is possible to split a scientific theory into its predictive rules of thumb on the one hand and its assertions about reality (sometimes known as its ‘interpretation’) on the other. This does not make sense, because – as with conjuring tricks – without an explanation it is impossible to recognize the circumstances under which a rule of thumb is supposed to apply. And it especially does not make sense in fundamental physics, because the predicted outcome of an observation is itself an unobserved physical process.

Many sciences have so far avoided this split, including most branches of physics – though relativity may have had a narrow escape, as I mentioned. Hence in, say, palaeontology, we do not speak of the existence of dinosaurs millions of years ago as being ‘an interpretation of our best theory of fossils’: we claim that it is the explanation of fossils.

Einstein resisted the fad, but the small group of positivist physicists working on quantum physics started teaching the “you are not allowed to ask the question” approach to their students. And that’s where things took a bad turn, because that approach is psychologically devastating. It effectively disables a powerful means of criticism and error correction.

Against Dawkins’ Middle World

Sam asks about evolutionary limitations of our capability to understand phenomena like quantum mechanics that happen at a scale so far beyond what we deal with day-to-day.

This is Richard Dawkins “Middle World”, and it’s a misunderstanding of our explanatory powers.

If scale was a limiting factor to our understanding, how come we have robust explanations that make accurate predictions for the behavior of stars and other celestial bodies—objects that are many orders of magnitude bigger and longer lived than what we humans deal with on a daily basis? And what about DNA—Dawkins’ area of expertise—isn’t it much smaller than what we evolved to manipulate? And isn’t evolution a process unfolding on a scale far beyond human lifespan?

David also points out that no other areas of physics seem to be affected by this supposed limit. General relativity is, in David’s opinion, far less intuitive, yet the conceptual shocks it brought were assimilated very fast—especially when physicists began to use the theory’s machinery instrumentally. The same happened with statistical mechanics.

Why David is convinced by the Many Worlds explanation of quantum mechanics

Sam asks: “When did you accept many worlds as the most plausible interpretation of quantum mechanics?”

David replies: “Not the most plausible, the only rational.”

This reveals the difference between believing a theory and understanding its explanation.

If a theory brings forward a good explanation and experiments verify it against alternatives, then you don’t need to accept or believe. You just need to understand.

On Realism

Realism is the philosophical theory that the world exists. It might not exist in the way that we see it, but we can understand it by the methods of observation, theory, and criticism.

Realism is the polar opposite of solipsism and nihilism.

Many worlds is a deeply realist theory, and there is no space for appeals to the supernatural like consciousness affecting the result of experiments.

David referred to a quote by Winston Churchill that sums up the contrast between realism and other worldviews that question objective reality. I tracked it down and I’m quite sure it’s the following, from Churchill’s My Early Life:

I am also at this point accustomed to reaffirm with emphasis my conviction that the sun is real, and also that it is hot – in fact as hot as Hell, and that if the metaphysicians doubt it they should go there and see.

Wheeler’s challenge

The great physicist John Wheeler supervised both Hugh Everett and David—at different times, of course.

He did not try to convince them of his ideas on quantum mechanics. His message was, “Give me an alternative. I want to understand quantum theory, if you think you can do better than Bohr and me, then go ahead and do it.”

Notice the difference between Wheeler’s attitude and that of the positivist teachers mentioned above.

Why others don’t accept Many-Worlds

David doesn’t answer the question directly, but remarks:

Because the human capacity for explanation is unlimited, so is the human capacity for error.

The thing that we have to ask is not how could they be led into such a large error, but how come they couldn’t be persuaded to come out of it.

David used to think this was a function of culture and upbringing, of the anti-rational memes that disable one’s capacity for error correction.

Dawkins’ favorite example for this phenomenon is god. Once you believe there’s a god that sees everything you do and think, that’s a disincentive to ever think deeply about whether its existence is possible.

[David:] I think the thing that has to become important to them to be easily persuadable of Everett, just like dinosaurs, is to care about reality.

Not just to care about what a particular theory will do for you, what it will protect you from, what it will comfort you about, and so on, but whether it describes reality or not, and to criticize it on those grounds and reject criticism on other grounds.

The majority of people working on quantum computers are Everettian because you need to deal with the nitty gritty of what is happening in different universes at different times in the calculation and it’s really hard not to think they are actually there, that they are merely a calculation tool.

The problem of many-worlds not being widely adopted, or rather, accepted, is sociological and David concludes, in yet another example of intellectual integrity, “I’m not really competent to judge.”

And he continues:

I’m most comfortable talking about what is true or not true. What is a good argument or a bad argument. Not why people believe strange things.

There are many more ways to be wrong than right, so we shouldn’t be surprised when others are wrong, and always on the lookout for when we could be wrong ourselves.

Constructor Theory

Constructor Theory is a different mode of explanation for physics. It does not rely on initial conditions. In this framework, the laws of motion are emergent properties. It’s really about what can be done and what can’t be.

See Chiara Marletto’s The Science of Can and Can’t for an introduction accessible to the layman.

Example of an impossible task: moving something faster than the speed of light.

Constructor theoretical quantum information, by identifying computations that are impossible, makes other computations possible. This is the power of constraints; a fascinating topic, but one for another time.

When Sam asks for how practical it might be to build a 50 qubit quantum computer, David replies, “I’m not an experimental physicist; I’m not competent to judge that.”

On LLMs and AGI

Sam: “How can you say that LLMs are not a path to AGI given you’ve been surprised by the progress they’ve made?” David: “We shouldn’t make conclusions for the things that have surprised me.”

But his explanation is that LLMs are sort of the opposite of what is required for AGI—or, at least, what one would expect to be required.

LLMs improve as they become more accurate and hallucinate less. That means narrowing the space of possible wrong things an LLM might do.

But for a true AGI, there can’t be any possible avenue of thought that’s off limits.

Also crucial to understand is that LLMs operate on existing knowledge, but a general intelligence, a universal explainer, is a knowledge creator.

Einstein’s explanations weren’t derived from existing knowledge or experiments. They came from solving problems. Special relativity was the result of how to reconcile the behavior of electromagnetic waves with Euclidean geometry. General relativity came from the problem of reconciling the existence of gravity with special relativity—every solution reveals new problems.

The alignment misconception

David suggests the G in AGI must be simple. After all, we are not that different from chimpanzees, but we are universal explainers and they are not.

When we do mental arithmetic, we’re not using the general intelligence part of the brain, but the more computational one. That’s why we’ve been able to offload computation to a calculator.

Unsurprisingly, Sam brings up Bostrom’s superintelligence explosion prophecy. Sam says “the devil is in the details.”

My reply would be: Exactly! Let’s talk about the details. Where will all the hardware come from? Especially given the current we need more compute trend. And what about the energy? We’ve so crippled our energy supply with green policies that we barely have enough energy to power our air conditioners in summer; how is the superintelligence going to power itself?

Sam compares the possible scenario to how it would feel to play against a chess engine that becomes better every ten minutes. David dismisses it saying that to win against Stockfish, one simply has to use Stockfish. It’s a software vs. hardware issue. Humans and AGI are, loosely speaking, software, and they can make use of the hardware.

Sam worries that AI is being developed “in the wild”. David again stresses the difference between AI and AGI. Based on his explanation of what general intelligence is, none of the current developments have much to do with AGI.

Sam keeps hammering on whether we’ll be able to “survive” a relationship with AGIs if/when they’ll come online. David reiterates that—at least in his vision—AGIs are people, as described in The Beginning of Infinity.

The existential danger we’d face with AGIs would be the same we currently face with other humans.

For Sam, the existential danger will be far worse if these thinking entities will be able to think faster and more coherently than us. David grants the point, but underscores that danger will materialize if the humans who will bring those AGIs online will teach them their bad intentions and bad morality. The danger will be if people who already have bad intentions and bad morality will be the first to create AGI and raise them that way.

On October 7th, antisemitism, and the future of the West

On October 7th and the appalling reaction of a surprisingly large part of the West, David shared his view, which he already elaborated in detail in The Pattern. Throughout history, there’s been a moral compulsion that legitimizes hurting (not necessarily killing) the Jews.

[David:] As a whole, I think the reason the West has got itself, what’s the word, gripped by the Pattern is, like I said, anything that gets sufficiently evil merges with the Pattern. So we have had post-modernism and woke and other bad philosophies that have kind of, as Gad Saad says [in his book The Parasitic Mind: How Infectious Ideas Are Killing Common Sense], parasitized, used the good-natured tolerance of the West to spread themselves.

And now it’s very hard to undo because there’s intimidation, there’s lack of freedom to discuss it openly, and so on.

So I think the West is in trouble.

I mean, I said I wouldn’t prophesy, so if I had to guess, I think the West will get out of this. It has got out of much worse before. But I don’t see how.

The only thing I would advocate is talking and one-to-one talking like we’re doing now. […]

And Criticism. Criticism and conjecture about what exactly is going on.

David is one of our most refined thinkers. When he talks, it’s worth listening.

You can find more of David’s interviews in my open source collection at https://mokagio.github.io/david-deutsch-anthology/ .